Monkey Around With ML and Library Data (Part 1)

In this post – and posts to follow – I’m going to be documenting what I learn about this current generation of Machine Learning and how it may be applied to library data.

I’m going to take a look at some of the history behind areas of AI and machine learning, and hopefully we can apply that history and background to that same type of work being done in libraries in the past and today.

Why Such a Sudden and Broad Interest in AI?

Firstly, let’s take a look at the where things are today with artificial intelligence. Things are moving VERY fast in this space as of this writing. Why is this? ChatGPT seems to be the most obvious answer to that question, but what is ChatGPT exactly, and what makes it so exciting and/or alarming to so many?

The “GPT” in ChatGPT stands for: Generative Pre-trained Transformer. The “Chat” is simply the interface – which is arguably what truly put this AI architecture on the map, making it practically a household name.

The models backing ChatGPT, and many other models like it, use a very effective and very new form of AI architecture called a Transformer.

To define what all this means exactly, we’ll start by defining some terms you may have heard being thrown around in relationship to AI recently.

Terms

Below is my attempt to define some terminology and provide an overview and establish a foothold in our learning.

Natural Language Processing (NLP)

NLP is a subfield of AI that focuses on the interaction between computers, and natural languages both spoken and written by humans.

The goal of NLP is to enable machines to understand, interpret, and generate responses to human language. This is done in such a way that systems can leverage it to extract meaning, answer questions, or provide other valuable insights from text (and other types of information – such as photos and audio – that may carry meaning).

Some specific tasks for NLP include

- Translation: Converting one language to another – English to German, French, etc.

- Sentiment Analysis: Determine if an input text is positive or negative. e.g. A review, or a social media post.

- Named Entity Recognition (NER) : Identify a personal name, or physical location name, in text.

- Question Answering: From a natural language query (e.g. a question written in English) answers or simple word/sentence completions are outputted from a given input text.

- Summarization: Input text is condensed down and made more succinct – similar to an abstract in an academic paper.

Natural Language Processing (NLP) enables computers to understand, interpret, and generate human language in a way that is both meaningful and useful.

Models

A machine learning model is a computational representation that captures patterns, relationships, or meaning from data. Models are pre-trained using algorithms acting on a dataset – often VERY large datasets. This allows the model to make ongoing predictions or ouputs without being explicitly programmed for the task. In other words, once trained, a model can generalize its knowledge to new, unseen data.

Models are, in essence, a way for a system to encapsulate what has been learned from data, and later re-apply that previous learning to unseen data

Transformer

The “Transformer” is a type of deep learning architecture introduced in the paper “Attention Is All You Need” by Vaswani et al. in 2017 (https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762). It has since become the foundation for many state-of-the-art models in natural language processing (NLP) tasks, such as translation, summarization, and question-answering.

There is also a popular open-source library from Hugging Face (huggingface.co) named “Transformers”

This Transformer library allows us to leverage a vast collection of pre-trained models that have been built with the Transformer architecture. It has grown to be a comprehensive library for a wide range of natural language processing (NLP) tasks and models. It has become a go-to resource in the NLP community due to its ease of use, extensive collection of pre-trained models, and active community support.

We’re going to be spending a lot of time later with the Transformer library, so we’ll move on for now.

Transformer architecture – introduced in 2017 – allows for models to be pre-trained on large datasets and fine-tuned on specific tasks. This approach has led to increased levels of simplicity and efficiency in terms of creating and training models – models are now able to be trained much more quickly across a wide range of NLP tasks.

Tokens / Tokenization

A token is a unit of text – it can represent a word, a sub word, a character, or even a sentence. Transformer-based models typically employ sophisticated tokenization methods for their specific use case. The Transformer library from huggingface.co includes tokenization methods that can be used with a specific transformer model selected for a Natural Language Processing (NLP) task.

For example, one transformer model named “BERT” (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) – a versatile model that has shown great performance on a wide range of NLP tasks – uses a tokenization method called WordPiece Tokenization. For the word “unaffordable”, the tokenizer might split it into sub words like:

1

["un", "##aff", "##ordable"]

Tokens are a unit of text, and Tokenization is a process by which a text is processed for use by transformer-based models (as well as other NLP models).

Vectors and Embeddings

Vectors

At a fundamental level, the output of transformers is in the form of vectors. The interpretation of these vectors varies based on the specific design of the transformer.

Vectors can represent entities such as the semantic information about words or sentences.

A vector is a mathematical entity that has both magnitude and direction, but in the context of NLP and machine learning, vectors are often just technically an ordered list of numbers that have specific meaning in the context of a transformer-based model.

Embeddings

Embeddings are very similar, but are subtly different from vectors. In terms of transformer-based models, embeddings refer specifically to the vector representation of items (e.g., words) in a way that captures the inherent relationships and semantic meanings of those items.

Items that are semantically or contextually similar will have embeddings that are close to each other in the vector space.

Let’s say we’re using a tiny version of BERT that produces embeddings in 3-dimensional space (in reality, BERT dimensional embeddings are much higher). Given the word “cat” in a sentence, the BERT model might produce an embedding like:

1

BERT("cat") # [0.723, −1.009, 0.567]

Given this embedding of the word “cat”, we can now take other words and generate embeddings to compare to. This allows us now to find:

- Synonyms or words with similar meanings:

- “kitten”

- “feline”

- Words that are related contextually:

- “pet”

- “meow”

- Words that often appear in similar contexts as “cat”:

- “whisker”

- “purr”

- Other related terms:

- “tomcat”

- “tabby”

Embeddings transform items, like words, into vector spaces where their positions capture semantic and contextual relationships.

Cosine Similarity

A cosine is a trigonometric function of an angle, commonly used in geometry and trigonometry to provide the ratio of the adjacent side to the hypotenuse in a right triangle. Cosine Similarity is a mathematical method used to compare two embeddings and determine how similar they are in N-dimensional space.

A cosine is a trigonometric function of an angle, commonly used in geometry and trigonometry to provide the ratio of the adjacent side to the hypotenuse in a right triangle. Cosine Similarity is a mathematical method used to compare two embeddings and determine how similar they are in N-dimensional space.

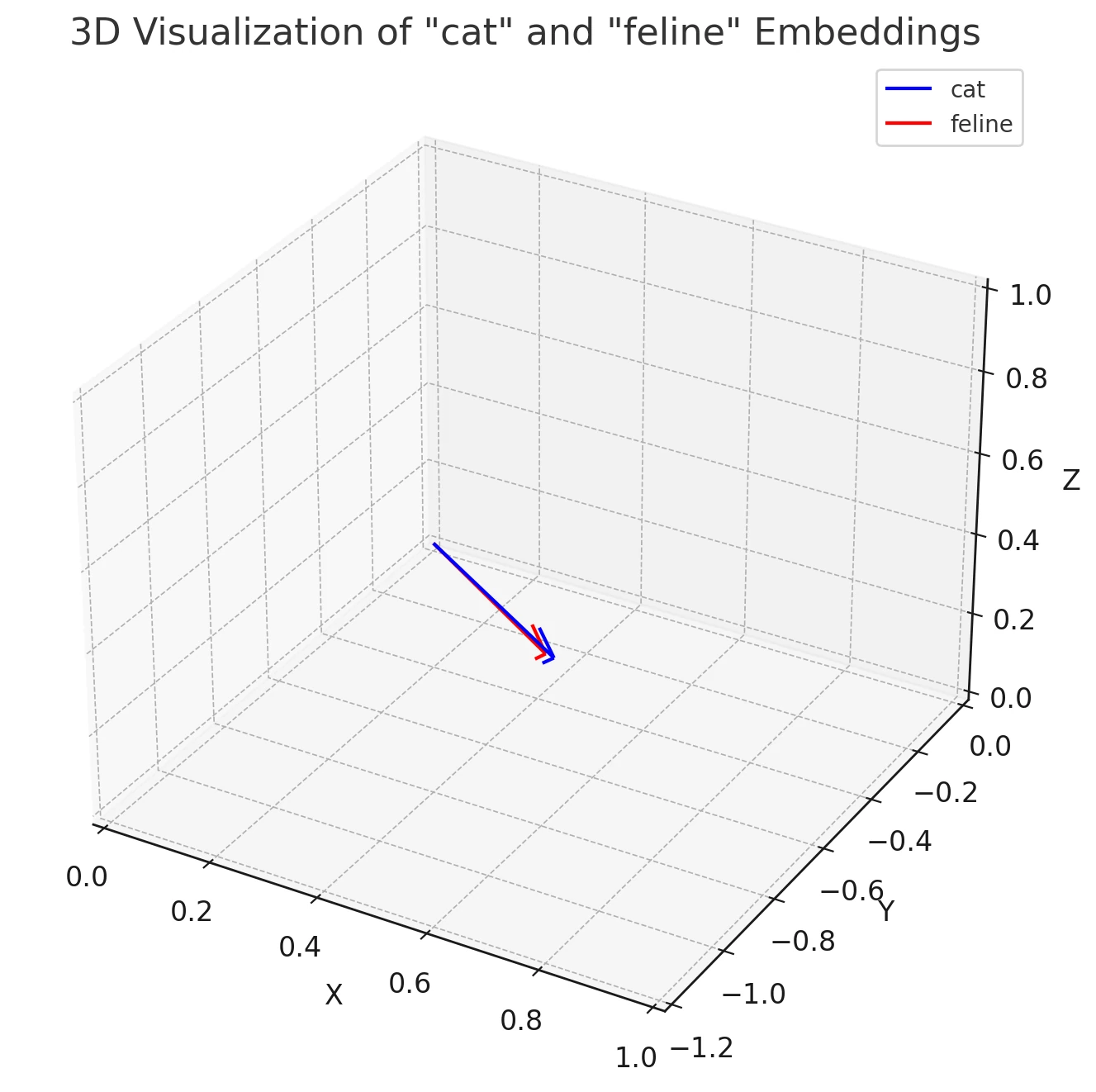

Comparing Vectors (and Embeddings) for Cosine Similarity

In our example above, using the word “cat”, we generated a vector using the tiny version of the BERT model. Now, for demonstration purposes, we can do the same, and produce a vector for the word “feline”:

1

2

BERT("cat") # [0.723, −1.009, 0.567]

BERT("feline") # [0.698, -0.987, 0.554]

For demonstrating cosine similarity between the vectors of these two words, “cat” and “feline” in a 3-dimensional space, we can use a plot of those two vectors. By examining the positions of these two vectors and considering the cosine of the angle between them in the 3D embedding space, we can see that they are very similar, indicating a close semantic meaning.

Using the metric of Cosine Similarity, we can discern that embeddings for semantically similar terms, like “cat” and “feline”, have a high degree of similarity in their representation.

Conclusion of Part 1

I plan on continuing with this exploration on a somewhat regular basis. However, if you’re eager to go deeper right now, I highly recommend exploring the works of Simon Willison. One particularly insightful blog post of his is “Embeddings: What they are and why they matter”, where he provides slides and a video from one of his amazingly insightful talks on transformer-based models. Another incredible talk from Simon can be found in his post titled “Making Large Language Models work for you”. A big “thanks” to Simon for making this topic more accessible and for his ongoing efforts in creating tools that make data exploration both fun and interesting!